The Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) in Mongolia and the Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Light Industry of Mongolia have finished implementing the ‘Green Gold and Animal Health Project’. We interviewed Project Manager Ts.Enkh-Amgalan on the project results.

Results and achievements of the ‘Green Gold and Animal Health Project’ have been presented to the Agriculture Ministry. What did Mongolia gain from the project?

-We deem that the project changed herders’ attitude towards pasture use. They have realized it is important to use pasturelands responsibly. Secondly, Mongolia has learned to identify the changes in pasture condition and desertification in a way the world can understand using the internationally accepted method. Finally, we introduced a national ‘standard for sustainable nomadic livestock production’. There used to be no standard for supply of animal products.

What are the characteristics of the standard?

-The ‘standard for sustainable nomadic livestock production’ indicates whether the animal raw material was sourced from fresh pasture, whether it is environmentally friendly, how responsible the herder was and what stages it went through from the herder’s pen to the factory. Countries around the world are introducing numerous sustainability standards. We introduced the abovementioned standard as Mongolia as a country of nomadic livestock husbandry had to have such standard. At our meetings with international traders, businesspeople, scientists and agricultural specialists, they often said, “If there could be a standard for sustainable nomadic livestock production, it would come only from Mongolia.”

Seizing the opportunity, we worked towards introducing a standard for sustainable nomadic livestock production. It was made possible not only as part of the Green Gold and Animal Health Project, but also with the cooperation of the Agriculture Ministry, and Mongolian researchers and agricultural specialists. The standard has been approved by the Mongolian Agency for Standardization and Metrology. What we need now is the government’s focus on its implementation.

How should the Agriculture Ministry continue the ‘Green Gold and Animal Health Project’?

-There has to be a distinct state policy on the proper use of pasture that has been missing for 30 years. It is also time for everyone to place emphasis on creating new jobs other than herding in rural areas. Herders and municipal employees of soums are the only people working in rural areas and there is no other job to choose. Therefore, there is a need to create a large number of jobs that supply and process animal raw materials, such as animal feed farming and organic food producing jobs.

Why did the project begin? It is said to have begun with aid provided for herders during the dzud of 1999-2000. Why was the project focus shifted to pasture?

-Yes it began during the dzud. At the time, SDC in collaboration with the United Nations Development Programme delivered financial and food aid to herders. We launched the project with a view to addressing overgrazing, herders’ livelihoods, and numerous other social and economic factors causing dzud. It started in view of the facts that pasturelands, where nomadic livestock farming is 100 percent based on, cover 70 percent of Mongolia’s total area, animal husbandry is one of Mongolia’s key economic sectors, and that pasture is the primary source of everything.

Pasture is also where even the project name Green Gold comes from. One time, when we mentioned eco pasture management in our conversation, a scientist who came from Switzerland said, “It seems the renewable pasture resource is the real gold in Mongolia”. We named the project as such afterwards. Now, when we say Green Gold, herders know we are talking about pasture.

One of the goals of the project was to also provide a research-based understanding of pasture degradation as researchers had different understandings of pasture and it was a controversial subject at the time. We refer to the changes observed in the pasture as it moves from one state to another by the term ‘pasture transition’ and identify what preventive measures are required and at what level the pasture degradation is through study.

For what reason scientists held differing understandings of pasture? What are the special features of your study?

-The differing understandings could be due to the transition period. Before the transition to a market economy, there was a pasture and fodder department in the Institute of Animal Husbandry where a team of scientists used to carry out a detailed study of the pasture and its plants and soil using the right method. They used the correct approach of studying the practices of herders who were responsibly using the pasture and reintroducing the practices after making research-based improvements. In other words, agriculture, animal husbandry, and pasture issues were at the center of state policies and when the economic system changes, the issues have been disregarded over the last 30 years. There is currently no policy, allocated budget, or a government body for pasture.

We have to restore the state policy on pasture that has been missing over the last 30 years.

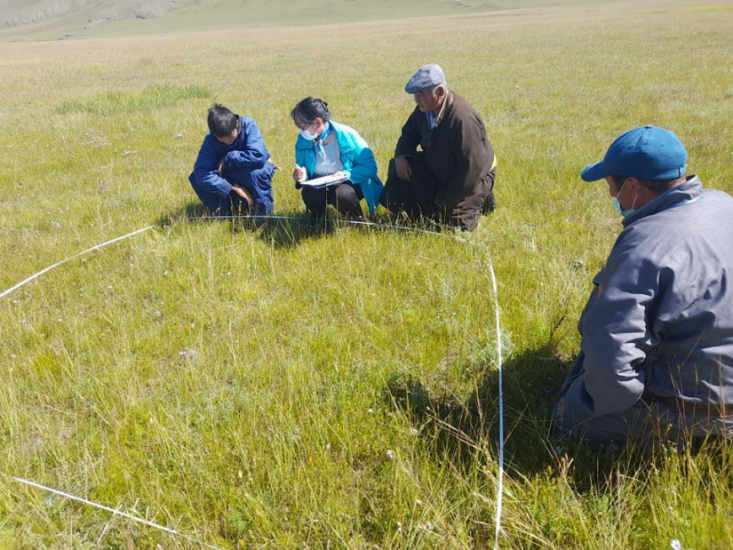

The study we conduct assists in evaluating the pasture degradation in a short period using more numerical data. Ultimately, we show the transition patterns to the herders and the local authorities.

What about the study method?

-We use a new method of pasture management and use studies designed for decision-makers. To develop the method, we conducted studies using the latest methodology used for monitoring rangeland health in Australia, New Zealand, and Inner Mongolia, China. The study focuses on the levels of three factors, the changes in the native plants of the pastureland, total area of the bare spots, and the pasture productivity, which is determined by the amount of plants per hectare, which are all shown in percentages, meaning there is very little inaccuracy. We assess overall rangeland health and degradation risk in a short period using the three measures.

The project focused on animal health besides the ‘green gold’. What is the role of veterinary services?

-Animal health is definitely connected to the overgrazing problem. The ‘standard for sustainable nomadic livestock production’ requires the animal to be healthy and the raw materials to be of high quality and standard. That is why we have worked to ensure more accessible and higher quality veterinary services for herders.

You previously mentioned the introduction of a standard for sustainable nomadic livestock production. The soccer ball made of yak leather is a great example. Have you started manufacturing it in large scale?

-We tested a number of products against the standard. One of them is the yak leather soccer ball. You can see QR codes on the soccer balls, which will let both the seller and buyer know about where the ball’s raw materials were sourced from, what herder from what place supplied the raw material to the factory, whether the product is environmentally friendly, and how responsible the herder was when grazing their livestock.

Leather products are in high demand on international markets. So Mongolia needs to make such products of high quality. The yak leather soccer ball paves the way for the production of more high quality leather products. We aimed to show that it is possible to mainly export quality products in any quantities to compete in the world market. There have been purchase orders for the soccer ball made of yak leather certified by the Responsible Nomads standard from abroad. The country that implemented the project, Switzerland has placed an order for a thousand balls.