Ts. Enkh-Amgalan (PhD) Daniel Miller

www.greenmongolia.mn wildyakman@gmail.com

https://maptia.com/danielmiller

About 72 percent of Mongolia’s total territory of 1.56 million square kilometers is considered grazing land; ranging from desert to desert-steppe, steppe, forest-steppe, taiga, and high mountain which provide forage for livestock, habitat for wildlife and important watershed functions. Mongolia has one of the largest, intact, temperate rangeland ecosystems in the world and a nomadic heritage thousands of years old.

As such, Mongolia has a unique opportunity to produce rangeland products (meat, fiber, hides and plants for herbal medicines, etc.) and environmental services (water, biodiversity, carbon sequestration, eco-tourism) to its citizens and to the world.

A key challenge Mongolia faces today is a decline in the health of the rangelands. This is due to an unprecedent increase in livestock numbers (a tripling of the total head of livestock to over 70 million now in just two decades!) leading to overgrazing and declining rangeland health or condition. The increase in livestock numbers has also led conflicts with wildlife, disputes over land use, and concerns about the sustainability of current livestock production practices.

Climate change, especially increasing temperatures and varying rainfall patterns, is also causing changes in vegetation. The growth in livestock numbers, climate change, and lack of effective range management in many areas threatens to damage the foundation of Mongolia’s nomadic heritage and the backbone of rural livelihood.

Rangelands are distinguished from pastures because they are primarily natural ecosystems with native vegetation rather than plants established by humans. Rangelands are typically managed principally with extensive practices, such as managed livestock grazing and prescribed fire, rather than more intensive agricultural practices of seeding, irrigation, and the use of fertilizers.

Understanding the ecology of Mongolia’s rangeland requires robust rangeland monitoring to determine their current condition or health. Monitoring is also needed to detect long-term changes that may have taken place with the vegetation. Information from monitoring programs can then be used to design appropriate rangeland and livestock management practices to sustain the rangelands.

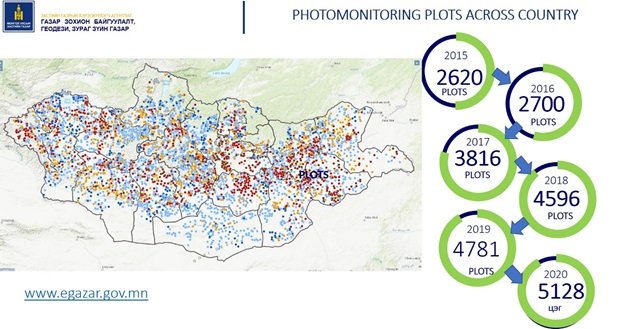

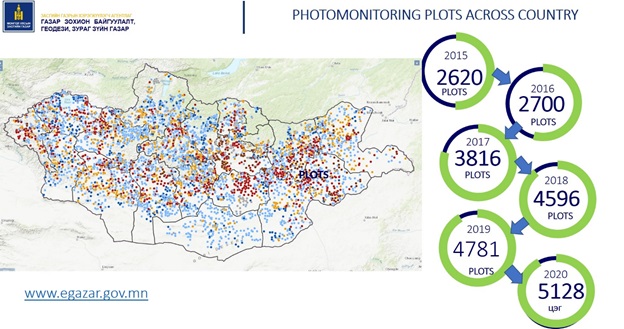

With their technical capacity strengthened by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation through the Green Gold project, Mongolia’s National Agency for Meteorology and Environmental Monitoring (NAMEM) and The Agency of Land Management, Geodesy and Cartography now implement comprehensive rangeland monitoring at 5100 sites and 1600 sites respectively across the country. New tools for interpreting rangeland health and developing site specific management recommendations called Ecological Site Descriptions (ESDs) and State and Transition Models (STMs) were developed by rangeland and soil scientists from Mongolian and international universities and research institutes and local agencies such as The Agency of Land Management, Geodesy and Cartography (ALMGaC) and NAMEM.

“ESDs and STMs are important because these tools define goals and measurable milestones for rangeland health. Without them, there can be no consensus on progress. We can also make many mistakes, such as managing toward unattainable goals for a specific land area and recommending flawed management prescriptions. ESDs and STMs create the local recipe book for rangeland health and sustainability.”

Brandon T. Bestelmeyer, Research Leader, USDA-ARS Range Management Research Unit, Las Cruces, New Mexico.

“The ecological site description concept and the “State and Transition Models for Mongolian Rangelands” are the primary tools for range monitoring and assessment, data analysis and interpretation of the health of the rangelands. ESD and STM concepts define the current state of rangeland health relative to the reference state and the potential shifts across the alternative states. Based on the ESD and STM concepts, rangeland ecosystem and grazing impact monitoring results, the needs for management changes should be diagnosed.”

Dr. D. Bulgamaa, Head of Research, Mongolian National Federation of Pasture User Groups of Herders.

National rangeland health reference database was created in 2015 at the NAMEM which provides the basis to define to what extent the rangelands have been altered and degraded from its ecological potentials. According to the First National Rangeland Health Assessment Report released in 2015 showing the state of rangeland health from its ecological potentials, 65 percent have been altered to some extent from a reference healthy condition. The National Rangeland Health Assessment Report is released every three years. According to the Second National Rangeland Health Assessment Report released in 2018, forty two percent of monitoring sites were judged to be in a “reference” or non-degraded state; 13.5 % in slightly degraded, 21.1 % in moderately degraded; 12.8 % in heavily degraded and 10.3 % in fully degraded level. Compared to the conditions assessed in 2014, the previous reporting year, the degree of degradation has increased in the last two years. The proportion of sites that were classified to a non to slightly degraded level has decreased by up to 10% while sites classified to heavily or fully degraded level has increased by 4.3-5.9%.

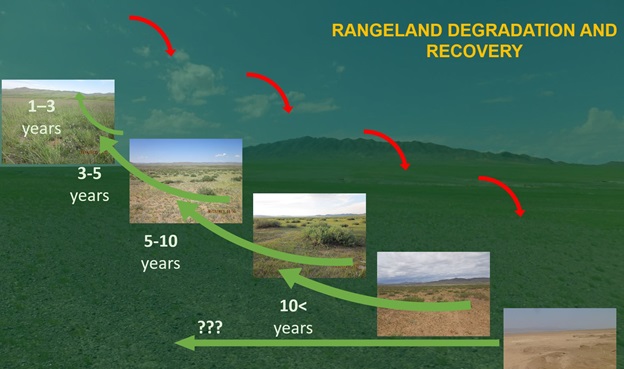

The good news is that many of the slightly altered rangelands have the potential to recover in 3-5 years through proper grazing management. But it is important to act decisively and promptly before those opportunities are lost.

“It is a very interesting exercise to do rangeland health photo monitoring. If we get herders to understand and cooperate, I witnessed that they will do their best to take good care of their land. I always tell herders that rangelands are their working place. If you take good care of your working place, you are the ones to benefit.”

A. Munkhtuya Altengerel, Land management Specialist, Dornod Aimag.

When you look at Mongolian rangelands it is fairly easy to see that some areas are different from other areas with regards to the vegetation, especially as to the kinds and amounts of plants. To understand this variation, these different areas are classified into units called Ecological Sites. An Ecological Site is defined as “a distinctive kind of land with specific characteristics that differs from other kinds of land in its ability to produce a distinctive kind and amount of vegetation”. Rangeland inventory and monitoring, analysis of data, and resulting range and livestock management decisions require the knowledge of these individual sites and their relationships on the landscape. The Ecological Site Description (ESD) provides detailed information about a particular kind of land - a distinctive Ecological Site. ESDs provide land managers the information needed for evaluating the land as to suitability for various land-uses, capability to respond to different management activities or disturbance processes, and ability to sustain productivity over the long term.

Mongolian rangelands are classified into 22 Ecological Site Groups (ESGs). There are five in the Forest Steppe Zone; five in the Steppe Zone; five in the Desert Steppe Zone; four in the Desert Zone; and three in the High Mountain Zone. Each of them has a “state-and-transition model” that describes how the rangeland has changed and how it can recover with improved management. The ESD concepts and state and transition models are approved by the Mongolian Academy of Sciences and used by government agencies as a management tool. State and transition models describe different states or health of rangelands based on a reference vegetation (healthy) and alternative states for specific types of soils and vegetation. Transition between states and vegetation community phases can be interpreted as degradation or restoration and related to specific management actions that can be used to prevent or reverse degradation over time.

Resilience-based rangeland management is now being implemented in many areas of Mongolia. It is focused on the sustainable production of meat, fiber, and other environmental goods and services from the rangelands. Resilience-based rangeland management enables herders, local officials, and rangeland managers to jointly identify range and livestock management problems and to recommend and implement improved management and other solutions to address the problems at the local level. It uses herders’ customary organizations such as Pasture User Groups (PUGs), herder groups and local government offices to implement range improvement programs and to monitor the rangelands.

There are now almost 98,000 herder households belonging to about 1,600 PUGs across Mongolia that are implementing resilience-based rangeland management plans. Manuals, technical guides, and user-friendly documents providing information about ecological sites descriptions and state-and-transition models assist herders and officials in monitoring rangelands and managing livestock grazing.

Most herders understand the need to reduce livestock numbers and adjust the number of animals they have to pasture stocking rates, but face challenges in knowing where to market animals. Training is needed for herders to make the transition from subsistence-based herding to producing livestock and livestock products for markets.

To improve the competitiveness of Mongolian livestock products, digital traceability system has been established and efforts are underway to assist herder families, cooperatives and processing plants for validation of livestock product origin and improved access for buyers to sustainably sourced products. Standard for Sustainable Code of Practices for nomadic livestock production in Mongolia, “Responsible Nomads” code of practices has been approved as a national standard in Mongolia. It is designed to validate and certify the quality and distinct properties of products originating from livestock raised on healthy, natural rangelands in the nomadic way of livestock herding.

D. Burmaa, Executive Director, Mongolian National Federation of PUGs of Herders

“The uniqueness of Mongolian nomadic herding practices has led a group of researchers and practitioners in consultation with herders to develop a Sustainable Code of Practices for nomadic livestock products. Over the centuries, nomadic herders have developed numerous experiences and knowledge in their endeavor to maintain a harmonious co-existence with the fragile and sensitive ecosystem of arid and semi-arid rangelands. The Responsible Nomads traceability system aims to incentivize herders to maintain sustainable rangeland and to live in harmony with wildlife. Responsible Nomads code of practices also incorporates animal health and animal welfare indicators that were selected together with herders, local specialists and researchers based on the context of nomadic herding and best practices that have evolved. The animal welfare indicators reflects the high resilience capacity of local breeds of livestock to the harsh climatic conditions of Mongolia.”

Mongolia has a long history of nomadic pastoralism, with herders raising livestock on the grasslands for thousands of years. Multi-species herds and mobility were and still are key aspects of livestock production and Mongolian herders have extensive traditional knowledge and understanding of the landscapes they use to raise livestock. Mongolian herders now face many challenges: an increase in livestock numbers, overgrazing, rangeland degradation, livestock diseases, climate change, and new markets. Herders will have to adapt to these changes to survive, but as long as they manage the rangelands and livestock well and combine the best aspects of their traditional practices and knowledge with appropriate science-based range and livestock management, Mongolian herders should be successful and have a bright future.